SETH CAMERON

SPOTLIGHT ON:

SETH CAMERON

The multi-hyphenate artist, educator, and founding member of the Bruce High Quality Foundation discusses his practice and gives us a glimpse into his new studio and its storied past.

Your practice has been quite multifaceted - how do you describe what you do?

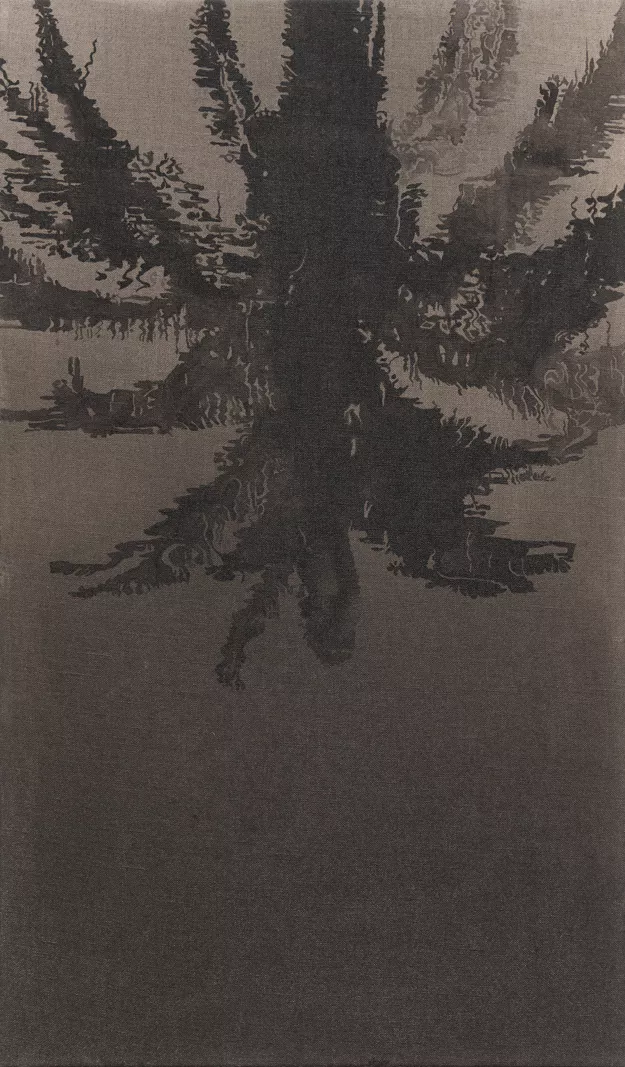

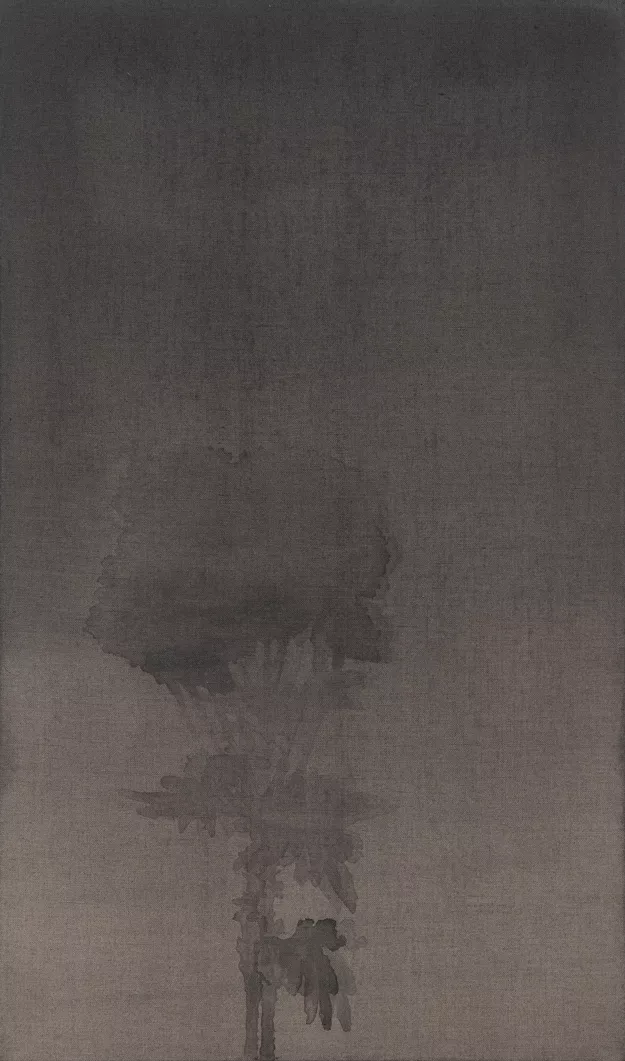

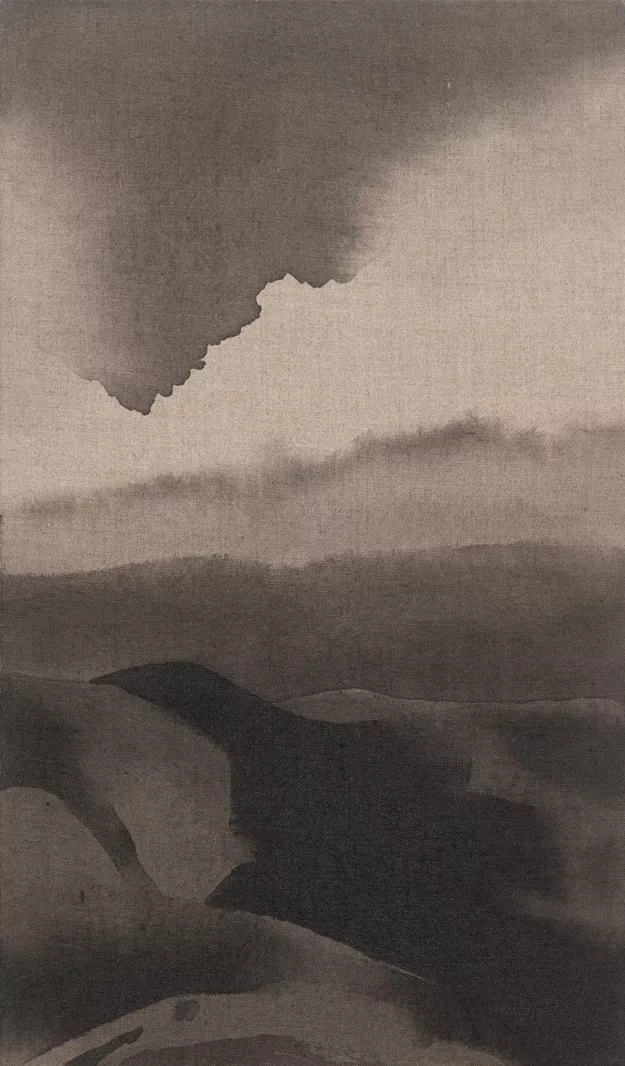

Ah! It’s useless. I make paintings. I make movies. I’ve scored musical theater productions for cats and built art schools for free. I do whatever I think needs doing and I’ve been doing it long enough now I can at least track how I move through ideas: I tend to be dialectical. I make work in response to work. For five or six years I made nothing but monochromes about color, and now I’m making images about images, about how they sucker us into stories and how much we depend on stories.

I move between disciplines as a way of staying outside the work, as a way of unsettling myself. It’s like how walking is just organized falling: you keep going so you don’t land on your face. So then, by happenstance my practice ends up looking “multifaceted,” “multidisciplinary,” “itinerant,” “styleless,” and “voyeuristic.” I won’t argue.

I might be called an “artist’s artist,” because what motivates me –before the specific emotional register of a work– is the problem of art itself – the impossible fact of it – the reality that, beyond any evolutionary, economic, or psychological exigency, art exists. I suppose this would qualify me as a religious artist. At least a zealot.

Speaking of which, I remember being in Sunday School as a kid and getting into a debate with the pastor – I think his name was Tony – about the irrationality of the Holy Trinity. How was I supposed to believe that 1) there is but one God, 2) the Father, Son and Holy Ghost are each, in themselves, God, and 3) they are not each other? And to Tony’s credit, he affirmed the paradox, telling me that to have faith in something rational wouldn’t be faith at all. I think this has informed my devotion to the tautology of “art for art’s sake.” There must be some critical aporia down at the bottom of things. It’s worth noting this was a Protestant church – those are my people all the way back – preachers and teachers of the Appalachian persuasion, and to this day I draw a straight line from the Protestant Reformation to “The Postmodern Condition.”

To date myself, I’ll note I came of age as an artist between 9/11 and the rise of Facebook, in the weird wheezing last gasp of scare quoting “identity” and “truth,” before the current wave of conspiratorial ideology took hold. Call me old fashioned, but I still don’t think art making is a search for truth – it’s something better than that.

Some of the paintings on Platform relate to Manet’s and Mondrian's florals. Tell us about that.

I was thinking about how grief abhors a vacuum. This was October, just after the attack in Israel, and I was thinking about how rage and justification and sentimentality and paranoia swoop in to eradicate the gutted nothingness of grief. But I wanted to sit with the nothingness of grief. I revisited Camus’ The Stranger for the masterclass, but narrativity felt wrong - I wanted to arrest grief somehow.

A thought occurred to me about arrested images, about Manet and Mondrian, the father figures of the triumphant march of austere Modernity - that for historians to make the case, they had to ignore the aberrations of each of their practices: the flower paintings. These works were excised from the story of Modernism through biography: Mondrian painted flowers “in secret,” or to make a buck. Manet did it while dying of syphilis. And now in our own time, these works have been “rescued from the dustheap” precisely because they are anomalies. They gain their pathos from their distance from “Painting,” from their closeness to cliche.

It occurred to me that grief is the shadow of pathos, the shadow of cliche – that the rituals of mourning are valuable for the emptiness of their gesture.

If you could collect any one artist, who would it be?

Ad Reinhardt and Thomas Merton went to college together, and corresponded all the while Merton was living as a Trappist monk in Gethsemane, Kentucky. Ardently atheist Ad even made a small black on black cruciform painting that Tom kept on the wall of his room in the monastery.

I’d live with that.

What’s your first memory of being impacted by art?

It was probably a hymn. I grew up in the United Methodist Church singing hymns every Sunday. Harmony, suspension and resolution were my first encounter, my first comprehension of an art experience.

The first time I experienced it in a painting must have been with a Kenneth Noland in the Greenville County Museum of Art in South Carolina. The painting is not too large, of a black ellipse ringed in periwinkle on a raw canvas square. It felt whole – like a hum.

What do you listen to while you work?

Yesterday it was Otis Redding, "Live at the Whisky a Go Go.” Today it’s Fleetwood Mac’s “Rumours.” In the car I’m listening to a lot of James Taylor for a film I’m working on about narcissism.

You’ve taught in various contexts. What are some key lessons you’ve learned and tried to pass on to your students?

The art critique is a far too dynamic experience to try to collapse into “key lessons.” It’s an immensely special, immensely rare kind of intimacy with an artist’s work. And they are going to hold on to unexpected traces from whatever you say to them.

I just try to be generous, try to let my thoughts develop in real time, and try to embody the joy of thinking critically about art work. I try to change my mind a lot in front of them. They need to feel a little stranded to know it’s their journey.

You recently set up a new studio in Connecticut with an interesting history - can you tell us a bit about that and how it’s affecting your practice?

The studio is a carriage house in Litchfield County, converted in the 60s by the German-American color field painter, Friedel Dzubas. Dzubas fled Nazi Germany in 1939, traveling to New York City, where he fell in with Helen Frankenthaler and the circle that would put on the Ninth Street Show in 1951, the legendary dawn of Abstract Expressionism. About a decade later, he became friendly with Clement Greenberg when the critic was looking for a place to summer outside the city. I found this picture of the two of them out front of the studio. Greenberg ended up including him in the iconic 1964 exhibition Post-painterly abstraction, alongside Gene Davis, Frankenthaler, Sam Gilliam, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella.

I’ve always felt connected to this moment of American painting – how it implicates aesthetic commitment in a larger story of human freedom. So it’s a pleasure to imagine Greenberg’s ghost sitting on my couch, petting my cat, and getting egregiously worked up at me for succumbing to images.

But more importantly, it’s just a beautiful studio. Nothing is an accident. The light is immaculate, the proportions are just right, the outlets are where they ought to be. It has a proletarian matter of factness that I find encouraging.

Where would you most like your work to be shown?

School. I hope the work outlasts the particulars of place and time, and contributes something to the development of other artists.

I’ve shown in plenty of museums and blue chip galleries, and, honestly, it doesn’t feel like anything. What feels real is meeting a younger artist whose own practice has developed in relationship, even antagonistically, to what I’ve done.