KALUP LINZY

SPOTLIGHT:

KALUP LINZY

The Tulsa-based artist is just as comfortable painting on a canvas as he is composing music to accompany his signature video work.

Photo courtesy of Tulsa Artist Fellowship/Melissa Lukenbaugh

What do you listen to while you work?

I have a lot of playlists on Spotify. I go from Nina Simone to Whitney Houston to Jill Scott to Erykah Badu to Boyz II Men. Sometimes it’s just classical instrumental music. Yesterday, I listened to Joy Harjo’s CD, she’s the US poet laureate and she’s also a Tulsa artist. On Sundays, I usually put on my vinyl. I have Anita Baker, Aretha Franklin, Diana Ross. I like jazz and old blues. I don’t know if I have B.B. King yet, but I had a blues playlist going two Sundays ago. It reminds me of being a kid when my aunt would host get-togethers on Sunday afternoons. Whenever I hear blues music, I always think of her and being a kid out in the yard.

Do you play instruments as well?

I play the keyboard and compose music. I grew up playing piano in church. I learned how to play by ear. I had some relatives start me off with lessons and show me the chord progressions, and from there I picked things up. When I was in high school, I was in band, and I remember they gave me the tuba to play. I remember carrying my tuba across campus and people were laughing at me, mainly my cousins and friends because I was so skinny that the tuba was bigger than me. I ended up quitting – the instrument was too heavy and I have asthma so didn’t really have the breath support to keep hitting the notes. I stuck with keyboard.

How important is music to your art?

It’s very much a part of my art. I’ve done a lot of visual music albums. Years ago, W Magazine covered me but in their music issue instead of their art issue. Then I did these collaborations with Proenza Schouler where they commissioned me to make music videos for two songs from my album starring Chloë Sevigny and Liya Kebede. I clearly remember that clicking in the fashion world, but it didn’t seem to cross back over to the art world. When I was collaborating with James Franco, we did an EP, but then we just went back to doing soap operas.

Now in Tulsa, I’m doing music recording with live musicians and instruments. Tulsa has a huge music culture, so it’s more efficient now. I’ll shoot a soap opera, and then I’ll lock myself in my bedroom and record an album in Garage Band. People were trying to get me to go to the studio years ago, but I like sitting here doing it instead of making it too polished. I was also afraid of losing control. I feel like my lyrics are specific to my character and how I wanted that narrative to go. Last year, I released a vinyl album called Paula Sungstrong Legend Recordings, and I released it on vinyl. It was a limited edition of 100 of the vinyl and 50 cassettes.

Why was it important to you to release that album in analog formats?

Being a performance artist, I feel like when museums do a show or exhibition they just want to include you in the programming, and it feels so fleeting. I felt it was getting to the point where even people in the art world were trying to push everything I was doing online. I want to be in these physical spaces. I really like things that are vintage. I thought creating this character that was vintage and releasing the album on vinyl and cassette felt like it would be something more special than streaming the album. And I like that people could go to their local record store.

One weekend, I took a trip to Bentonville and Eureka Springs. During that trip, I got a call from Josey Records, the music store. They wanted me to send them more vinyl because they ran out. They only take two or three at a time. Taylor Hanson from the Hanson brothers, who live in Tulsa, bought the last one. Those sorts of discoveries where people stumble across it, I like that. I don’t want every aspect of my work to be virtual.

Do you think the nostalgia of stumbling upon things in an organic way is the reason vinyl and even CDs are having a resurgence?

I don’t know if it’s just nostalgia. My music and my work are finding a new audience with these 20-year-olds who were born in ‘94, ‘95, so there’s no way they were around when vinyl was originally around in the ‘70s. But vinyl had a comeback in the ‘90s, too. They were babies when I was recording songs with my cassette player. This record label called Cult Love Sound Tapes who I collaborated with on the cassette, they’re like 25- and 26-year-olds and they have a cassette tape label. It’s a new generation into cassettes, and they sell out.

Do you think that the new generation is discovering these things because of the internet and YouTube?

Yeah, it’s all happening at once. My world would have been a lot bigger if we’d had the internet. There would have been far more options for influences to be part of my artistic DNA. I think these kids can find whatever they gravitate toward and create a community.

You’re already so multidisciplinary, but are there any new skills you’re learning?

I collaborate with fashion designers, and I’m trying to launch my own label but haven’t been able to yet. People told me years ago I should start my own fashion line, but I didn’t want critics to tear me apart. I’ve collaborated with DVF and Proenza Schouler and always wondered how they were creating season in, season out, and I got a little intimidated. I’ve been trying to figure out how to do it the last two years and then the pandemic kind of slowed it down. That’s something I’m hoping I can launch in a year or two.

I just signed a contract to buy a house so it can be an artist residency that’ll have three to four artists a year that I’ll host. I’ve done over a dozen artist residencies, and every time I’ve done one, I wonder how it would look if I had my own. I’m trying to figure out the most effective way it would resonate with communities, be an extension of my own work and also support emerging artists who are starting out. I want to give back and get to those dreams I haven’t been able to get to.

A friend of mine has a new show coming out on FX called Reservation Dogs and I’ve been on the set doing background work, but I want to do more in television on that level. Ten or 11 years ago, I did General Hospital with James Franco. I could have just gone on set and learned, but I was living in Brooklyn and that was LA, so I felt like I didn’t take full advantage to learn another side of things. In college, we had film, but I didn’t study film from the industry’s point of view. I still want to shoot a feature film.

Why do you think now is the time to explore these projects you’ve been thinking about for so long?

I feel like I’ve reached a daytime audience, but I don’t think the art world was deep into General Hospital. I realized with my art house, it’s now or never. Even though I’m recognized in some circles, when one or two generations pass, some people might have no idea who you are. It’s like when I get interviewed by magazines and I tell the same stories over and over. But I realized you have to keep repeating those stories for a new generation or else it gets lost after 5 to 10 years.

With my music, I got to Tulsa, and I thought if you want something different to happen, you have to do something different. I started going into the studio with the band because I didn’t feel so much pressure. I don’t have the angst I had in my 20s like I have to do everything right now or else I’m going to get left behind. That is totally gone.

A lot of the things you mentioned have to do with being remembered. Is the idea of legacy important to you?

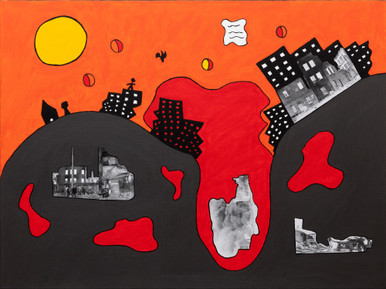

Yeah, it is important. I had an ancestry genetic test done, and now I’m going to be making collages of my characters exploring my own ancestry. I have pictures of my mom and aunts and might start incorporating them into it. I don’t think I’m going to have any biological kids at this point, so my DNA is going to stop with me. Hopefully, my artistic DNA will be out there. Also, the art house. I thought one way I could have an impact on artists was doing an artist residency where those who come to it can be mentored. I don’t know what my legacy will be, but I definitely want to leave something behind where I can say, “I was here.”

Would you rather know what the future holds or be surprised?

I don’t think I want to know what the future holds, but I love listening to feelings about things. If you let a bad feeling fester and grow, that’s going to become your future. When I was in New York all the time, people kept telling me I made it, but every time I was in a space I was putting myself somewhere else. That’s the reality I was creating where I was never settled. I was always looking to the next thing. People come to you and ask what’s next, but sometimes I want to marinate in the present.

What do you wish you were asked more often?

I feel like in some interviews, certain things about real life stuff will be brushed off like there’s no interest. I grew up raised by my grandmother because my mother was on drugs and mentally ill. When I would mention it, it seems like there’s less of an interest, but that’s part of my experience that makes up who I am and why I became an artist. If my mother wasn’t mentally ill and on drugs and I wasn’t raised by my grandmother, if I grew up in a two-parent home and everyone was happy, I don’t know if I would have pursued art. It’s not to put a damper on everything or bring the mood down, but those experiences shaped me as a person and an artist and it has given me a certain perspective on life.

A lot of people think my characters are me, but a lot of my characters are just in my imagination or something I hoped for and emotions I experienced. It’s not just one thing. It’s not me just telling something verbatim from an experience. Because it’s all those things, I don’t think people will ever be able to put their finger on it. I want people to be OK with the totality of those past experiences growing up and not feeling like it’s a downer or I’m sad. Those things aren’t the case, but I draw from some of that stuff. Those dreams, those hopes carried me through. I hope people would ask those sorts of things without being put off by them.